Sino-Vietnamese War

| Sino–Vietnamese War (Third Indochina War) Associated with the Cold War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

China |

Vietnam |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 200,000+ PLA infantry and 400 tanks from Kunming and Guangzhou Military District[1] |

60,000 regular force, 150,000 local troops and militia [2] |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Chinese claim: 6,900 killed, 15,000 wounded.[3] Western source: 26,000 killed, 37,000 wounded and 420 tanks destroyed [1] |

Western source: 20,000 killed, 32,000 wounded and 185 tanks destroyed[4] Vietnam claims: 10,000 civilians killed, not figures of military [1] |

||||||

|

|||||

The Sino–Vietnamese War (Vietnamese: Chiến tranh biên giới Việt-Trung), also known as the Third Indochina War, known in the PRC as 对越自卫反击战 (duì yuè zìwèi fǎnjī zhàn) (Counterattack against Vietnam in Self-Defense) and in Vietnam as Chiến tranh chống bành trướng Trung Hoa (War against Chinese expansionism), was a brief but bloody border war fought in 1979 between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. The PRC launched the offensive in response to Vietnam's invasion and occupation of Cambodia, which ended the reign of the PRC-backed Khmer Rouge.

After a brief incursion into Northern Vietnam, PRC troops withdrew about a month later. Both China and Vietnam claimed victory in the last of the Indochina Wars of the twentieth century; however, since Vietnamese troops remained in Cambodia until 1989 it can be said that the PRC failed to achieve the goal of dissuading Vietnam from involvement in Cambodia. However, China achieved its strategic objective of reducing the offensive capability of Vietnam along the Sino-Vietnam border by implementing a scorched earth policy. China also achieved another strategic objective of demonstrating to its Cold War foe, the Soviet Union, that they were unable to protect their Vietnamese ally. As many as 1.5 million Chinese troops were stationed along China's borders with the USSR and were prepared for a full-scale war against the USSR.

Contents |

Historical background

France Vs Vietnam: First Indochina War

Vietnam first became a French colony when France invaded in 1858. By the 1880s, the French had expanded their sphere of influence in Southeast Asia to include all of Vietnam, and by 1893 both Laos and Cambodia had become French colonies as well.[5] Rebellions against the French colonial power were common up to World War I. The European war heightened revolutionary sentiment in Southeast Asia, and the independence-minded population rallied around revolutionaries such as Hồ Chí Minh and others, including royalists.

Prior to their attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese occupied French Indochina.[6][7] The Japanese surrender in 1945 created a power vacuum in Indochina, as the various political factions scrambled for control.

The events leading to the First Indochina War are subject to historical contention.[8] When the Viet Minh hastily sought to establish the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the remaining French at first welcomed the new regime, but then staged a coup to regain their control.[7][9] The Kuomintang supported French restoration, but Viet Minh efforts towards independence were backed by Chinese communists. The Soviet Union at first supported French hegemony, but later supported Hồ Chí Minh.[10][11] The Soviets nonetheless remained less supportive than China.

The war itself involved numerous events that had major impacts throughout Indochina. Two major conferences were held to bring about a resolution. Finally, on July 20, 1954, the Geneva Conference (1954) resulted in a political settlement to reunite the country, signed with support from China, Russia, and Western European powers.[12] While the Soviet Union played a constructive role in the agreement, it again was not as involved as China.[10][13] The U.S. disapproved of the agreement and swiftly moved when the Vietnamese gained their independence.

Sino–Soviet split

The Chinese Communist Party and the Viet Minh had a long history. During the initial stages of the First Indochina War with France, the recently founded communist People's Republic of China and the Viet Minh had close ties. In early 1950, China became the first country in the world to recognise the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, and the 'Chinese Military Advisory Group' under Wei Guoqing played an important role in the Viet Minh victory over the French.

After the death of Stalin, relations between the Soviet Union and China began to deteriorate. Mao Zedong believed the new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev had made a serious error in his Secret Speech denouncing Stalin, and criticized the Soviet Union's interpretation of Marxism-Leninism, in particular Khrushchev's support for peaceful co-existence and its interpretation. This led to increasingly hostile relations, and eventually the Sino-Soviet split. Until Khrushchev was deposed in late 1964, North Vietnam supported China in the dispute, mainly as a result of China's support for its re-unification policy, whereas the Soviet Union remained indifferent. From early 1965 onwards, Vietnamese communists drifted towards the Soviet Union, as now both the Soviet Union and China supplied arms to North Vietnam during their war against South Vietnam and the United States.

US War in Vietnam: Second Indochina War

The Soviets welcomed the Vietnamese drift toward the USSR, seeing Vietnam as a way to demonstrate that they were the "real power" behind communism in the Far East.

To the PRC, the Soviet-Vietnamese relationship was a disturbing development. It seemed to them that the Soviets were trying to encircle China.

The PRC started talks with the USA in the early 1970s, culminating in high level meetings with Henry Kissinger and later Richard Nixon. These meetings contributed to a re-orientation of Chinese foreign policy towards the United States. Meanwhile, the PRC also supported the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. The PRC supported Pol Pot from fear that a unified Vietnam, in alliance with the Soviet Union, would dominate Indochina.

Cambodia

Although the Vietnamese Communists and the Khmer Rouge had previously cooperated, the relationship deteriorated when Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot came to power and established Democratic Kampuchea. The Cambodian regime demanded that certain tracts of land be "returned" to Cambodia, lands that had been "lost" centuries earlier. Unsurprisingly, the Vietnamese refused the demands. According to Vietnam, Pol Pot responded by massacring ethnic Vietnamese inside Cambodia (see History of Cambodia), and, by 1978, allegedly supporting a Vietnamese guerrilla army making incursions into western Vietnam. However, it should be noted that Pol Pot massacred people of all races, including ethnic Chinese, ethnic Vietnamese and Cambodians.

Realizing that Cambodia was being supported by the PRC, Vietnam approached the Soviets about possible actions. The Soviets saw this as a major opportunity. The Vietnamese army, relatively fresh from combat with the forces of the United States, would easily be able to defeat the Cambodian forces. This would not only remove the only major PRC-aligned political force in the area but also demonstrate the benefits of being aligned with the USSR. The Vietnamese were equally excited about the potential outcome. Laos was already a strong ally; if Cambodia could be "turned," Vietnam would emerge as a major regional power, political master of Indochina.

The Vietnamese feared reprisals from the PRC. Over a period of several months in 1978, the Soviets made it clear that they were supporting the Vietnamese against Cambodian incursions. They felt this political show of force would keep the Chinese out of any sort of direct confrontation, allowing the Vietnamese and Cambodians to fight out what was to some extent a Sino-Soviet war by proxy.

In late 1978, the Vietnamese military invaded Cambodia. As expected, their experienced and well-equipped troops had little difficulty defeating the Khmer Rouge forces. On January 7, 1979, Vietnamese-backed Cambodian forces seized Phnom Penh, thus ending the Khmer Rouge regime.

PRC vs. Vietnam: Third Indochina War

While the first war emerged from the complex situation following WWII and the second exploded from the unresolved aftermath of political relations with the first, the Third Indochina War again followed the unsolved problems of the earlier wars. The fact remains that: "Peace did not come to Indochina with either American 1973 withdrawal or Hanoi's 1975 victory" as disputes erupted over Cambodia and relations with China.[14]

The PRC, now under Deng Xiaoping, was starting the Chinese economic reform and opening trade with NATO nations, in turn, growing increasingly defiant against the USSR. On November 3, 1978, the USSR and Vietnam signed a twenty-five year mutual defense treaty[15], which made Vietnam the "linchpin" in the USSR's "drive to contain China." [16]

On January 1, 1979, Deng Xiaoping visited the USA for the first time and spoke to American president Jimmy Carter: "Children who don't listen have to be spanked." (original Chinese words: 小朋友不听话,该打打屁股了。).[17] On February 15, the first day that China could have officially announced the termination of the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance, Deng Xiaoping declared that China planned to conduct a limited attack on Vietnam.

The reason cited for the counter strike was the mistreatment of Vietnam's ethnic Chinese minority and the Vietnamese occupation of the Spratly Islands (claimed by the PRC). To prevent Soviet intervention on Vietnam's behalf, Deng warned Moscow the next day that China was prepared for a full-scale war against the USSR; in preparation for this conflict, China put all of its troops along the Sino-Soviet border on an emergency war alert, set up a new military command in Xinjiang, and even evacuated an estimated 300,000 civilians from the Sino-Soviet border.[18] In addition, the bulk of China's active forces (as many as one-and-a-half million troops) were stationed along China's borders with the USSR.[19].

In response to China's attack, the USSR sent several naval vessels and initiated a Soviet arms airlift to Vietnam. However the USSR felt that there was simply no way that they could directly support Vietnam against the PRC; the distances were too great to be an effective ally, and any sort of reinforcements would have to cross territory controlled by the PRC or U.S. allies. The only realistic option would be to indirectly re-start the simmering border war with China in the north. Vietnam was important to Soviet policy but not enough for the Soviets to go to war over. When Moscow did not intervene, Beijing publicly proclaimed that the USSR had broken its numerous promises to assist Vietnam. The USSR's failure to support Vietnam emboldened China to announce on April 3, 1979, that it intended to terminate the 1950 Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance.[15]

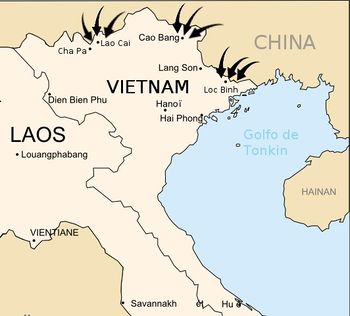

Chinese forces

Two days after the declaration of war, on February 17, a PRC force of about 200,000 supported by 200 Type 59, Type 62, and Type 63 tanks from the PRC People's Liberation Army (PLA) entered northern Vietnam.[20] The Chinese force consisted of units from the Kunming Military Region (later abolished), Chengdu Military Region, Wuhan Military Region (later abolished) and Guangzhou Military Region, but commanded by the headquarters of Kunming Military Region on the western front and Guangzhou Military Region in the eastern front.

Some troops engaged in this war, especially engineering units, railway corps, logistical units and antiaircraft units, had been assigned to assist Vietnam in its struggle against the United States just a few years earlier during the Vietnam War. Contrary to the belief that over 600,000 Chinese troops entered Vietnam, the actual number was only 200,000. However, 600,000 Chinese troops were mobilized, of which 200,000 were deployed away from their original bases during the one month conflict. Around 400 tanks (specifically Type 59s) were also deployed.

The Chinese troop deployments were observed by US spy satellites, and the KH-9 Big Bird photographic reconnaissance satellite played an important role. In his state visit to the US in 1979, the Chinese paramount leader Deng Xiaoping was presented with this information and asked to confirm the numbers. He replied that the information was completely accurate. After this public confirmation in the U.S., the domestic Chinese media were finally allowed to report on these deployments.

Chinese order of battle

- Guangxi Direction (East Front) commanded by the Front Headquarter of Guangzhou Military Region in Nanning. Commander-Xu Shiyou, Political Commissar-Xiang Zhonghua, Chief of Staff-Zhou Deli

- North Group: Commander-Ou Zhifu (Deputy Commander of Guangzhou Military Region)

- 41st Corps Commander-Zhang Xudeng, Political Commissar-Liu Zhanrong

- 121st Infantry Division Commander-Zheng Wenshui

- 122nd Infantry Division Commander-Li Xinliang

- 123rd Infantry Division Commander-Li Peijiang

- 41st Corps Commander-Zhang Xudeng, Political Commissar-Liu Zhanrong

- South Group: Commander-Wu Zhong (Deputy Commander of Guangzhou Military Region)

- 42nd Corps Commander-Wei Huajie, Political Commissar-Xun Li

- 124th Infantry Division Commander-Gu Hui

- 125th Infantry Division

- 126th Infantry Division

- 42nd Corps Commander-Wei Huajie, Political Commissar-Xun Li

- East Group: Commander-Jiang Xieyuan (Deputy Commander of Guangzhou Military Region)

- 55th Corps Commander-Zhu Yuehua, Temporary Political Commissar-Guo Changzeng

- 163rd Infantry Division Commander-Bian Guixiang, Political Commissar-Wu Enqing, Chief of Staff-Xing Shizhong

- 164th Infantry Division Commander-Xiao Xuchu (also Deputy Commander of 55th Corps)

- 165th Infantry Division

- 1st Artillery Division

- 55th Corps Commander-Zhu Yuehua, Temporary Political Commissar-Guo Changzeng

- Reserve Group (came from Wuhan Military Region except 50th Corps from Chengdu Military Region), Deputy Commander-Han Huaizhi (Commander of 54th Corps)

- 43rd Corp Commander-Zhu Chuanyu, Temporary Political Commissar-Zhao Shengchang

- 127th Infantry Division Commander-Zhang Wannian (also as the Deputy Commander of 43rd Corps)

- 128th Infantry Division

- 129th Infantry Division

- 54th Corsp Commander-Han Huaizhi (pluralism), Political Commissar-Zhu Zhiwei

- 160th Infantry Division (commanded by 41st Corp in this war) Commander-Zhang Zhixin, Political Commissar-Li Zhaogui

- 161st Infantry Division

- 162nd Infantry Division Commander-Li Jiulong

- 50th Corps Temporary Commander-Liu Guangtong, Political Commissar-Gao Xingyao

- 148th Infantry Division

- 150th Infantry Division

- 20th Corps (only dispatched the 58th Division into the war)

- 58th Infantry Division (commanded by the 50th Corps during the war)

- 43rd Corp Commander-Zhu Chuanyu, Temporary Political Commissar-Zhao Shengchang

- Guangxi Military Region (as a provincial military region) Commander-Zhao Xinran Chief of Staff-Yin Xi

- 1st Regiment of Frontier Defense in Youyiguan Pass

- 2nd Regiment of Frontier Defense in Baise District

- 3rd Regiment of Frontier Defense in Fangcheng County

- The Independent Infantry Division of Guangxi Military Region

- Air Force of Guangzhou Military Region (armed patrol in the sky of Guangxi, did not see combat)

- 7th Air Force Corp

- 13th Air Force Division (aerotransport unit came from Hubei province)

- 70th Antiaircraft Artillery Division

- The 217 Fleet of South Sea Fleet

- 8th Navy Aviation Division

- The Independent Tank Regiment of Guangzhou Military Region

- 83rd Bateau Boat Regiment

- 84th Bateau Boat Regiment

- North Group: Commander-Ou Zhifu (Deputy Commander of Guangzhou Military Region)

- Yunnan Direction (the West Front) commanded by the Front Headquarter of Kunming Military Region in Kaiyuan. Commander-Yang Dezhi, Political Commissar-Liu Zhijian, Chief of Staff-Sun Ganqing

- 11th Corp(consisted of two divisions) Commander-Chen Jiagui, Political Commissar-Zhang Qi

- 31st Infantry Division

- 32nd Infantry Division

- 13th Corps(camed from Chengdu Military Region) Commander-Yan Shouqing, Political Commissar-Qiao Xueting

- 37th Infantry Division

- 38th Infantry Division

- 39th Infantry Division

- 14th Corp Commander-Zhang Jinghua, Political Commissar-Fan Xinyou

- 40th Infantry Division

- 41st Infantry Division

- 42nd Infantry Division

- 149th Infantry Division (from Chengdu Military Region, belonged to 50th Corps, assigned to Yunnan Direction during the war)

- Yunnan Military Region (as a provincial military region)

- 11th Regiment of Frontier Defense in Maguan County

- 12th Regiment of Frontier Defense in Malipo County

- 13th Regiment of Frontier Defense in

- 14th Regiment of Frontier Defense in

- The Independent Infantry Division of Yunnan Military Region commanded by 11th Corps in the war

- 65th Antiaircraft Artillery Division

- 4th Artillery Division

- Independent Tank Regiment of Kunming Military Region

- 86th Bateau Boat Regiment

- 23rd Logistic Branch consisted of five army service stations, six hospitals, eleven medical establishments)

- 17th Automobile Regiment commanded by 13th Corps during the war

- 22nd Automobile Regiment

- 5th Air Force Corps

- 44th Air Force Division (fighter unit)

- Independent unit of 27th Air Force Division

- 15th Air Force Antiaircraft Artillery Division

- 11th Corp(consisted of two divisions) Commander-Chen Jiagui, Political Commissar-Zhang Qi

Vietnamese forces

Many of Vietnam's elite troops were in Cambodia keeping a tight grip on its newly occupied territory. The Vietnamese government claimed they left only a force of about 70,000 including several army regular divisions in its northern area. However, the Chinese claimed to have encountered more than twice this number. During the war, Vietnamese forces also used American military equipment abandoned during the Vietnam War.

Course of the war

The Chinese entered Northern Vietnam and advanced quickly about 15-20 kilometers into Vietnam, with fighting mainly occurring in the provinces of Cao Bang, Lao Cai and Lang Son. The Vietnamese avoided mobilizing their regular divisions, and held back some 300,000 troops for the defence of Hanoi. The Vietnamese forces tried to avoid direct combat, and often used guerrilla tactics. The initial Chinese attack soon lost its progress, and a new wave of attack was sent in. Eight Chinese divisions joined the battle, and captured some of the northernmost cities in Vietnam. After capturing the northern heights above Lang Son, the Chinese surrounded and paused in front of the city in order to lure the Vietnamese into reinforcing it with units from Cambodia. This had been the main strategic ploy in the Chinese war plan as Deng did not want to risk an escalation involving the Soviets. The PVA high command, after a tip-off from Soviet satellite intelligence, was able to see through the trap, however, and committed reserves only to Hanoi. Once this became clear to the PLA, the war was practically over. An assault was still mounted on the PVA 314A division defending the city. The Chinese failed to use artillery effectively, and suffered heavy casualties.[21] After three days of bloody house-to-house fighting, Lang Son fell on March 6. The PLA then took the southern heights above Lang Son[22] and occupied Saba. By now, the PLA could claim to have crushed several of Vietcong's regular units including the 316A Infantry Division, the 308th Infantry Division, the 3rd Infantry Division, the 345th Infantry Division and the 346th Infantry Division[23], but they also suffered extensive casualties themselves. The communist government of Vietnam had chosen to flee from Hanoi to the city of Huế, 540 kilometers to the south[24], but the combination of high casualties, a badly organized commando, harsh Vietnamese resistance and the risk of the Soviet entering the conflict stopped the Chinese from going any further. On march 6, China declared that the gate to Hanoi was open and that their punitive mission had been achieved. On the way back to Chinese border, the PLA destroyed all local infrastructure and housing and looted all useful equipment and resources (including livestock), completely paralyzing the economy of northern Vietnam[23]. The PLA crossed the border back into China on March 16. It remains disputed whether or not the gate to Hanoi was actually open, considering the 300,000 troops ready to defend the city. While China claimed to have crushed the Vietnamese resistance, Vietnam claimed that China almost only had fought against border militias. This allowed both sides to claim military victory, as both sides claimed to have taught their opponent a lesson.[25]

Chinese casualties

To this day, both sides of the conflict describe themselves as the victor. The number of casualties is disputed, with some Western sources putting PLA losses at more than 20,000 killed throughout the war. Chinese democracy activist Wei Jingsheng told western media in 1980 the Chinese troops had suffered 9,000 deaths and more than 10,000 wounded during the war [26], but the recent source leaked out shows that PLA had 6,954 dead and 14,800 wounded[23] , 238 Prisoners of War [27] throughout the war.

Vietnamese casualties

There are no independently verifiable details of Vietnamese casualties; like their counterparts in the Chinese government, the Vietnamese government has never announced any information on its actual military casualties. The Nhan Dan newspaper[24] the Central Organ of the Communist Party of Vietnam claimed that Vietnam suffered more than 10,000 civilian deaths during the Chinese invasion[24] and earlier on May 17, 1979, reported statistics on heavy losses of industry and agriculture properties[24].

Vietnamese armed personnel:

Regular forces : 20,000 killed in total, Wounded: more than 10,000. 2210 Prisoners of War [23][28] Province Militia and divisions of the Public Security Army: unknown, the total causality estimated: 70,000[29]

China's tactical flaws and strategic objectives

The Chinese military was using equipment and tactics from the era of the Long March, World War II and the Korean War. Under Deng's order, China did not use their naval power and air force to suppress enemy fire, neutralize strong points, and support their ground forces. Therefore, the Chinese ground forces were forced into absorbing the impact of Vietnamese firepower.[30] The PLA lacked adequate communications, transport, and logistics. Further, they were burdened with an elaborate and archaic command structure which proved inefficient in the FEBA (Forward Edge of Battle Area).[31]

Runners were employed to relay orders because there were few radios—those that they did have were not secure. The Cultural Revolution had significantly weakened Chinese industry, and military hardware produced suffered from poor quality, and thus did not perform well. These shortcomings did not stop the PLA from executing all its tactical plans. The strategic goal of rescuing China's Khmer Rouge allies, however, failed completely. Vietnam was able to occupy the whole of Cambodia soon afterward.

Aftermath

The legacy of the war is lasting. China and Vietnam each lost thousands of troops, and China lost 3,446 million yuan in overhead, which delayed completion of their 1979-80 economic plan.[32] To reduce Vietnam's military capability against China, the Chinese implemented a "scorched-earth policy" while returning to China. They caused extensive damage to the Vietnamese countryside and infrastructure, through the destruction of Vietnamese villages, roads and railroads.[33] The war did not alter Vietnamese policy in Cambodia; the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia was still ousted and replaced by a new government. The Chinese were forcibly reminded of their troops' lack of training and tactical coordination after 10 years of the Cultural Revolution in China during 1966 to 1976.[32]

Border skirmishes continued throughout the 1980s, including a significant skirmish in April 1984. Armed conflict only ended in 1989 after the Vietnamese agreed to fully withdraw from Cambodia, this also saw the first use of the Type 81 assault rifle by the Chinese and a naval battle over the Spratly Islands in 1988. In 1999 after many years of negotiations, China and Vietnam signed a border pact, though the line of demarcation remained secret.[34] There was a very slight adjustment of the land border, resulting in land being given up to China, which caused the widespread complaints within Vietnam[35]. Vietnam's official news service reported the implementation of the new border around August 2001. Again in January 2009 the border demarcation with markers was officially completed, signed by Deputy Foreign Minister Vu Dung on the Vietnamese side and his Chinese counterpart, Wu Dawei, on the Chinese side.[36] Both the Paracel (Hoàng Sa: Vietnamese) (Xīshā: Chinese) and Spratly (Trường Sa: Vietnamese) (Nangsha: Chinese) islands remain a point of contention.[37]

The Vietnamese government continuously requested an official apology from the Chinese government for its invasion of Vietnam but the Chinese government refused. After the normalization of relations between the two countries in 1990, Vietnam officially dropped its demand for an apology.

Relations after the war

The December 2007 announcement of a plan to build a Hanoi-Kunming highway was a landmark in Sino-Vietnamese relations. The road will traverse the border that once served as a battleground. It should contribute to demilitarizing the border region, as well as facilitating trade and industrial cooperation between the nations.[38]

Reflections from international and Chinese media

On March 1, 2005, Howard W. French wrote in The New York Times: Some historians stated that the war was started by Mr. Deng(China's then paramount leader Deng Xiaoping) to keep the army preoccupied while he consolidated power, eliminating leftist rivals from the Maoist era and Chinese soldiers were used as cannon fodder in a cynical political game. He cites author and war veteran Xu Ke who wrote that the soldiers were sacrificed for politics, and it's not just me who feels this way - lots of comrades do, and we communicate our thoughts via the Internet. [...] The attitude of the country is not to mention this old, sad history because things are pretty stable with Vietnam now. But it is also because the reasons given for the war back then just wouldn't stand now.[39]

The Chinese official name for the war was 对越自卫反击战 (duì yuè zìwèi fǎnjī zhàn), roughly translated as 'self-defense counterattack against Vietnam'.

Chinese media

There are a number of Chinese songs, movies and TV programs depicting and discussing this conflict with Vietnam in 1979 from the Chinese viewpoint.[40][41][42] These vary from the patriotic song "Bloodstained Glory" originally written to laud the sacrifice and service of the Chinese military, to the 1986 film The Big Parade which carried (as far as possible, in the China of the time) veiled criticism of the war.

See also

- Battle of the Paracel Islands

- Johnson South Reef Skirmish

- Sino-Soviet border conflict

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Zhang Xiaoming, (actually are thought to have been 200,000 with 400 - 550 tanks)"China's 1979 War with Vietnam: A Reassessment", China Quarterly, Issue no. 184 (December 2005), pp. 851-874. Zhang writes that: "Existing scholarship tends towards an estimate of as many as 25,000 PLA killed in action and another 37,000 wounded. Recently available Chinese sources categorize the PLA’s losses as 6,900 dead and some 15,000 injured, giving a total of 21,900 casualties from an invasion force of 200,000."

- ↑ King V. Chen(1987):China's War With Việt Nam, 1979. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University, page 103

- ↑ 《对越自卫反击作战工作总结》Work summary on counter strike (1979-1987) published by The rear services of Chinese Kunming Military Region http://mil.chinaiiss.org/content/2008-10-6/619729_2.shtml

- ↑ King V. Chen(1987):China's War With Việt Nam, 1979. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University, page 114

- ↑ Dunnigan, J.F. & Nofi, A.A. (1999). Dirty Little Secrets of the Vietnam War. New York: St. Martins Press, p. 27.

- ↑ Dunnigan, J.F. & Nofi, A.A. (1999). Dirty Little Secrets of the Vietnam War. New York: St. Martins Press, pp. 27-38.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hood, S.J. (1992). Dragons Entangled: Indochina and the China-Vietnam War. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, p. 16.

- ↑ Burns, R.D. and Leitenberg, M. (1984). The Wars in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, 1945-1982: A Bibliographic Guide. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio Information Services, p.xx.

- ↑ Burns, R.D. and Leitenberg, M. (1984). The Wars in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, 1945-1982: A Bibliographic Guide. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio Information Services, p. xx.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Hood, S.J. (1992). Dragons Entangled: Indochina and the China-Vietnam War. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, p. 13-19.

- ↑ Chen, Min. (1992). The Strategic Triangle and Regional Conflict: Lessons from the Indochina Wars. Boulder: Lnne Reinner Publications, p. 17-23.

- ↑ Hood, S.J. (1992). Dragons Entangled: Indochina and the China-Vietnam War. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, p. 13-19.

- ↑ Chen, Min. (1992). The Strategic Triangle and Regional Conflict: Lessons from the Indochina Wars. Boulder: Lnne Reinner Publications, p. 17-23.

- ↑ Burns, R.D. and Leitenberg, M. (1984). The Wars in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, 1945-1982: A Bibliographic Guide. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio Information Services, p. xxvi.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 {http://www.vietnam.ttu.edu/vietnamcenter/events/1996_Symposium/96papers/elleviet.htm Sino-Soviet Relations and the February 1979 Sino-Vietnamese Conflict by Bruce Elleman}

- ↑ Scalapino, Robert A. (1982) "The Political Influence of the USSR in Asia" In Zagoria, Donald S. (editor) (1982) Soviet Policy in East Asia Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, page 71.

- ↑ "In Chinese:中共對侵越戰爭八股自辯". http://www.hkfront.org/wcvcw12.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-23.

- ↑ {(Chang Pao-min, Kampuchea Between China and Vietnam (Singapore, Singapore University Press, 1985), 88-89.)}

- ↑ {(Robert A. Scalapino "Asia in a Global Context: Strategic Issue for the Soviet Union," in Richard H. Solomon and Masataka Kosaka, eds., The Soviet Far East Military Buildup (Dover, MA. , Auburn House Publishing Company, 1986), 28.) }

- ↑ ChinaDefense.com - The Political History of Sino-Vietnamese War of 1979, and the Chinese Concept of Active Defense

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Armchair General magazine

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 《对越自卫反击作战工作总结》Work summary on counter strike (1979-1987) published by The rear services of Chinese Kunming Military Region http://mil.chinaiiss.org/content/2008-10-6/619729_2.shtml

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Nhan Dan newspaperhttp://www.nhandan.org.vn/english/

- ↑ http://faroutliers.wordpress.com/2009/02/04/what-the-pla-learned-in-vietnam-1979/

- ↑ www.voanews.com voice of America

- ↑ 《中越战俘生活实录》 life of prison camp from count strike war, Shi Wenying, published by spring breeze literature press in March, 1991.http://book.lrbook.com/showbook.jsp?dxNumber=000000275010&d=6984E042AF

- ↑ 《中越战俘生活实录》 life of prison camp from count strike war, Shi Wenying, published by spring breeze literature press in March,1991.http://book.kongfz.com/10202/80282768/

- ↑ 《许世友的最后一战》The last fight of General Xu Shiyou, Zhou Deli,Jiangshu People's press , June,1990 http://book.kongfz.com/13519/75509646/ http://www.docin.com/p-5824062.html

- ↑ The Chinese Communist: Air Force in the "Punitive" War Against Vietnam

- ↑ ocp28 - The Chinese People's Liberation Army: "Short Arms and Slow Legs"

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "China "Should Learn from its Losses" in the War against Vietnam" from "1st August" Radio, People's republic of China, 1400 GMT, 17 February 1980, as reported by BBC Summary of World Broadcasts, 22 february 1980

- ↑ History 1615: War and Peace in the 20th Century

- ↑ BBC News | ASIA-PACIFIC | China-Vietnam pact signed

- ↑ www.bbc.co.uk

- ↑ Thanh Nien News | Politics | Vietnam, China complete historic border demarcation

- ↑ Thanh Nien News | Politics | Vietnam reiterates sovereignty over archipelagoes

- ↑ Greenlees, Donald Approval near for Vietnam-China highway International Herald Tribune, 13 December 2007

- ↑ French, Howard W. (March 1, 2005). "Was the War Pointless? China Shows How to Bury It". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/01/international/asia/01malipo.html?pagewanted=2&_r=2&8hpib&oref=slogin. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ http://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%AD%E8%B6%8A%E6%88%98%E4%BA%89#.E4.B8.AD.E5.9B.BD.E5.A4.A7.E9.99.86

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ka-zqQ5vHI&feature=related

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HvMnHy7LuPE

External links

- Global Security Analysis of the Sino-Vietnamese War

- Order of Battle

- Air Power in the War

- G.D.Bakshi: The Sino–Vietnam War — 1979: Case Studies in Limited Wars

Additional sources

- In Chinese:外国专家点评中国对越自卫反击战的战略战术 Translation:The PLA's war strategy and tactic in the eye of western experts

- Chinese:对越自卫反击战Google translation

- In Chinese:对越自卫反击战:我军大量伤亡原因分析Google translation

- In Chinese:中国对越自卫反击战中为何不进攻河内?Google translation

- In Chinese:关于请求落实部分军队退役人员有关政策的报告Google translation

- In Chinese:法卡山没有划归越南,主峰归属中国一方Google translation

- In Chinese:委屈太大,收复法卡山战斗被推迟的原因Google translation

- In Chinese:新中国战役之------中越之战Google translation

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||